Lex Shady & Chris Tobin

There is a quote that we believe represents the vast majority of the fire service concerning buildings; it reads,

“Many an object is not seen, though it falls within the range of our visual ray, because it does not come within the range of our intellectual ray.” Thoreau, Henry

Simply put, we all see buildings, but few understand what they’re actually looking at. That’s a problem, a really big problem for two important reasons: a building is the one thing that directly or indirectly affects everything we do on the fire ground and the only thing we can do about a compromised building is avoid it entirely. We show up with no solution to sagging roofs, crumbling walls, or missing floors other than staying away. We can mitigate smoke, fire, and rescue trapped victims, but we can do nothing about the leaning wall. It’s this stark reality that many forget and have paid the price. You can know all there is about fire behavior, your tools and strategies, none of which hold any value if you’re unfamiliar with the space in which they are relied upon. Some may say all fires are the same, which is true until you put one in a building. Behind every door are an infinite amount of variables, some known, some unknown and some unexpected. This is why nothing’s routine till it’s over and why knowing your buildings on a visceral level is paramount. If you want to be able to forward think, you must understand the data you’re receiving.

This will be a five part series exclusively examining five different types of legacy construction, each with its own article as it pertains to firefighting. The types of buildings were selected based on their prominence in today’s main streets and historic districts. These specific types of buildings exist in small towns from coast to coast but are more commonly found East of the Mississippi River where our national building stock originated before moving Westward.

The five buildings are the old house, the taxpayer, the old mill, the vacant theater, and the bowling alley. Each of these will be examined along with inherent hazards and a play book for handling fires specific to each occupancy. Additionally since many of these buildings are found in small towns with departments that may not have the adequate resources, there will be a section based on short staffed responses for each. The objective of this series is to present the most useful amount of information in the least amount of space. Each of these buildings are worthy of their own book themselves; this series is meant to be concise and simple information for any level of firefighter. As with any article on architecture, regional vernacular and departmental jargon may vary. Nothing in this piece is the final say, only the individual reader and their streets can make that claim.

Part 1

The Building

The old house: The older single family homes in historic districts and around Main streets come in a countless styles and forms, from large ornate Victorians that line avenues owned by early prominent landowners to small shotgun bungalows within walking distance to factories facilitating the local workforce. The majority of what we see today are legacy framed or masonry brick buildings dating from the 1850s-1930s. Due to their abundance and because the other buildings in this series are all commonly of masonry construction, this section will address specifically wood framed houses. Access to railroads for Eastern timber played a pivotal role in how early or late your areas legacy building stock will be. A towns layout also determined what type of structure would be built. Long narrow urban lots would be best suited for gable front or shotgun style houses while wider ones would accommodate “I-Houses,” two rooms wide and one room deep. Most legacy frame houses were multi-story with half-storied gable windows or dormers of some sort. These buildings are easily identified from the exterior by stone foundations, center chimneys, wood siding, transoms, long narrow windows, metal roofs, and upper floor window AC units are common due to sub par centralized air.

The Hazards

The inherent architectural hazards in old legacy homes starts in the framing. With access to timber and saw mills these “mass planned” homes went up fast with balloon framing techniques taking the place of rough cut post and beam. The fire spread in balloon framing is nothing new to firefighters. The continuous stud bay existing from basement to attic creates a direct avenue of fire extension that can blow past floors of unsuspecting occupants and the unprepared fireman. Balloon framing ended in the 1940s and was replaced with today’s platform framing. The classic indicators of balloon framing are, long stacked windows sharing the same stud bay, stone foundation and center chimney placement. Beware of modern additions to the exterior of these houses such as garages or sun rooms. This will create an interior balloon framed wall that was originally an outside one.

In addition to the framing voids created, legacy homes contained older lumber. Go into an old attic and rub your finger on a ceiling joist, you’ll find what appears to be charcoal like dust. The structural members in these places are subject to what’s called pyrophoric carbonization. The wood is slowly oxidizing, losing moisture and thus burns more intensely due to lower ignition temperatures than expected. Many a fire has been started by a lightbulb being hung too close to a century’s old piece of lumber.

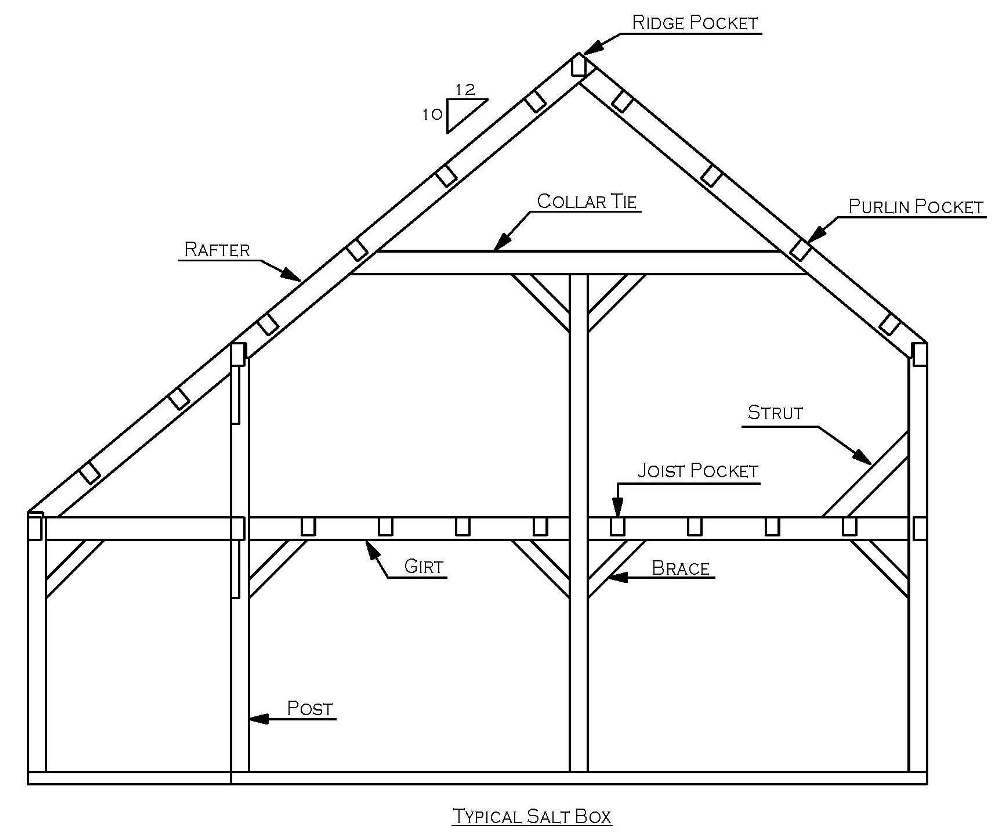

The layouts of these homes present some challenges to firemen. Two sets of stairs would be common, one main set near the entrance and smaller set in the rear off the kitchen called “servants stairs.” A common roof style is the “ saltbox or catslide” depending on your region, which poses a significant upper floor fire spread potential via the roof soffit. In addition some lesser known hazards are pocket doors, window transoms, laundry chutes, tin ceilings, metal roofs and combustible varnished wall coverings. These are all things to be cognizant of during firefighting operations.

The Playbook

Three words, hold the stairs! These buildings are almost always multiple stories with the bedrooms up stairs. The stairs and egress paths must be your strategic priority, fire heat and smoke will naturally be drawn up the stairs and into the sleeping areas above. If there are servants stairs this task will be doubled but no less important. Keep an eye out for a side entrance, these were common and offered access to the basement and second floor stairs from one location. The first line off must address this without delay. Any time paused outside is more time the upper floors are filling with deadly byproducts of combustion. Confinement is key in legacy wood framed houses, search teams need to be aggressively diligent in getting above and ahead of hose lines if conditions permit in order to close doors and start overhaul concurrently with fire attack. Keep in mind if you VES and close the door for confinement there may be a failed transom window above, a high scan with a TIC should address this.

Ventilation in these buildings should play off the compartmented nature of their design. This means hydraulic ventilation by the hose team will be much more effective than the wide area floor plans seen in modern homes. This also allows extinguishment, overhaul and ventilation to be done simultaneously with one or two crews in the area of origin. Careful with PPV early on, as the many voids will give way to some very undesirable conditions. Fans should be used only in conjunction with overhaul well after the fires under control. Due to the prevalence of hip and gabled roofs, vertical ventilation is a common tactic for top floor fires containing knee walls. Understand you’re venting voids not living space.

Since these buildings are compartmentalized by design a single 1.75 hose line flowing 150gpm will do considerable knockdown to multiple rooms or even multiple floors of fire. Even so, as a regular precaution a second line should be put advanced to the upper floors for cutting off extension. This line can be dry stretched initially to get it in place quicker to upper floors.

Maneuverability wins the day in these buildings. If conditions require a large amount of water on arrival, choose the deck gun before the 2.5 if possible. Trying to advance a large diameter line to upper floors inside a building with numerous small rooms creating corners will be futile. A well off fire will out pace your advance regardless of your available GPM. Save the 2.5 for defensive operations or exposure protection.

Once the main body of fire is knocked, overhaul needs to start in two places as simultaneously as possible. Once in the room of origin, and the bathroom or kitchen closest to the fire. Plaster and lath walls and ceilings are common and need to be overhauled appropriately by working the connections along a stud, rafter or joist. Kitchens and bathrooms are important to immediately check due to the presence of “wet walls,” or the wall that contains the plumbing and vents creating a pipe chase. These walls are even more important when they’re directly above the fire floor or any fire in the basement. A general rule of thumb for overhauling in legacy construction is fire in the floor, open the wall. Fire in the wall, open the ceiling. Fire in the ceiling, open the baseboards on the floor above. These are fires you must stay ahead of by understanding where they’re going before it gets there. This forward thinking is the difference between evacuation tones and a quickly extinguished fire.

The Short Staffed Response

The initial response to an “old house” fire for a short staffed department includes the same actions as that of an urban department. The initial attack line gets stretched, water is pumped, and command is established. It has the potential to get complicated when your initial response consists of anywhere from 2-6 personnel. If your initial response does not have adequate manpower to complete tasks safely, your attack choices are made for you until additional personnel arrive. The only exception to this rule is for rescues, with confirmed or suspected entrapment departments must search.

As we talked about before, protecting the stairs can make or break how quickly you beat the fire. With low man power you may have to make an educated guess as to where the fire is, and make a choice as to which set of stairs to protect. Another line must be stretched to the second set of stairs as soon as manpower allows. The wrong choice can have dire consequences, so understanding fire behavior and fire spread in your old homes is extremely important.

Then there are the “other” tasks that must be completed at every fire. Manpower and the scene will dictate the tasks that are prioritized. Officers must be capable of reading fire behavior and be able to quickly and correctly prioritize tasks across their members. Understanding the construction of the homes in your district will help you with these decisions. It is imperative that officers know their crews strengths and weaknesses and assigns tasks appropriately.

Without the luxury of having specific companies your members will need to be cross trained and capable of completing all of the tasks a fire requires. Frequently, members will be responsible for more than one task. An example of this could be your initial attack team also completing the primary search. Nozzle man focuses on the fire, and the second man quickly searches rooms and closes doors as they advance. Engineers must be comfortable pumping tank water to the first line, and then establishing their own water supply. Communication and speed are crucial.

Pre-planned mutual aid agreements may be beneficial. Having mutual aid departments automatically dispatched to your fires allows the officer to focus on the fire in front of them instead of worrying about what resources he or she will need to request from mutual aid – help is already coming. Recall for members and mutual aid from surrounding departments can take anywhere from 5-20 minutes on a good day, which is great for manpower on longer scenes, but doesn’t help for initial response tactics. You’ll still need them though, as you’ll need to provide your members with a chance to rest.

Old house fires also come with the potential for it to be a rural fire which adds an entirely new set of complications. Rapid response and establishing adequate water supply early are the keys to success for these scenes. This is where pre-planning of your district is extremely important. The officer and driver must be aware of where the closest hydrant or dry hydrant is and be able to rapidly establish a tanker shuttle if necessary. Tank water can get you a long way, but with delayed response due to travel times, it may not be enough. Don’t be afraid to call for help. It’s better to have too many on scene and send them home, than not enough. You can’t put out a fire if you run out of water.

Regardless of department size or response, legacy wood framed buildings require strategic foresee-ability on arrival. A wood framed building and its seven sides of fire spread have been the thorn in many a Chiefs side. The old houses that exist in every small town, in every state, demand a certain level of respect that has been lost to modern lightweight construction in the name of a penny. These homes were built to last and will test every skill set a firefighter claims to have. Never forget the reality is, no matter how much you know, where you work, or how good you think you, are the simple fact remains; the building does not care.